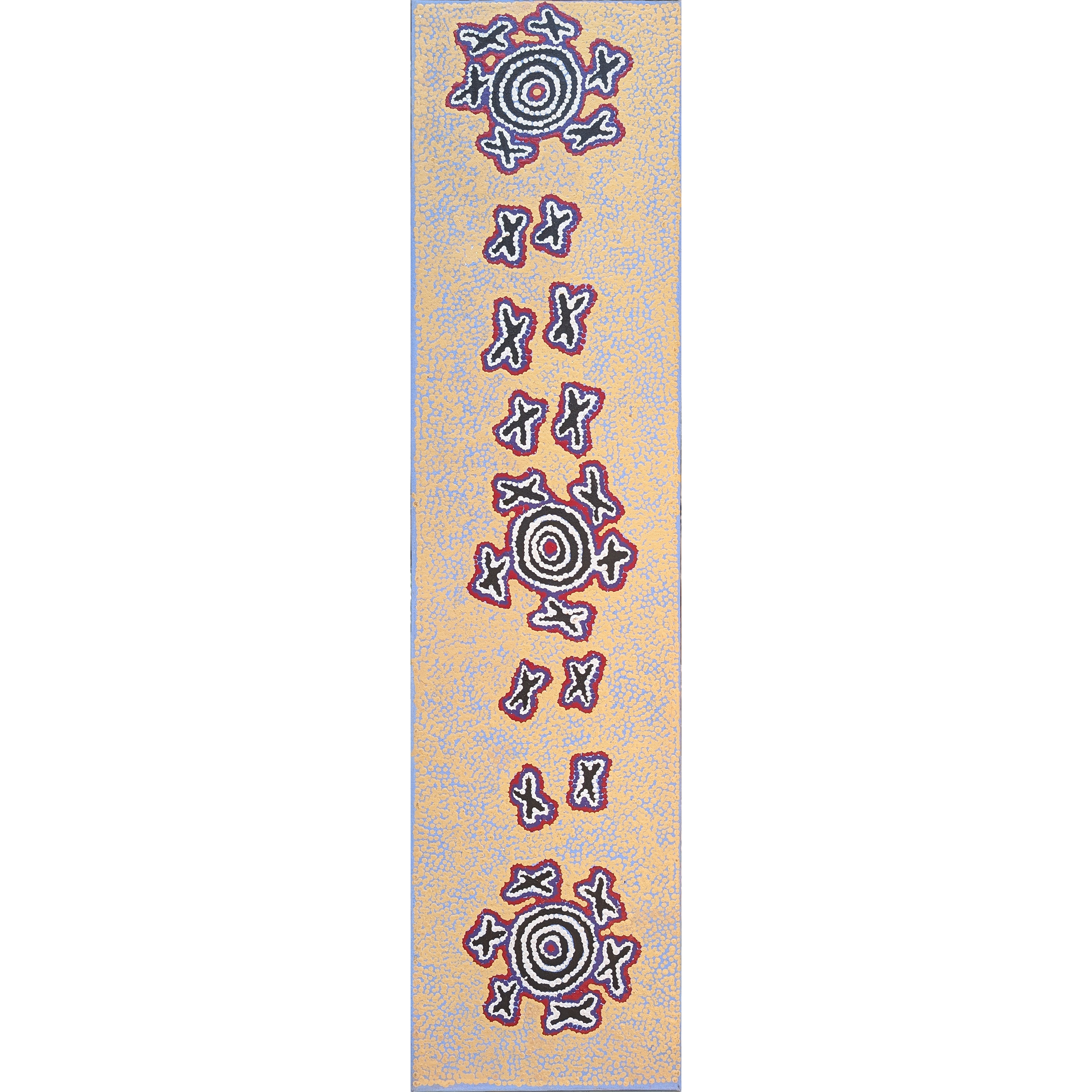

Artist: Paddy Japaljarri Stewart | Title: Green Budgerigar Dreaming | Year: 2005 | Medium: Acrylic on Belgian Linen | Dimensions: 121 x 30cm

PROVENANCE

Warlukurlangu Artists Cat No. 1443/05

ARTWORK STORY

The country of the Dreaming is garlu east of Yuendumu, near Mount Allen, where a Dreamtime Jungarrayi man (Lintipilinti) fell in love with a Napangardi woman, his classificatory mother -in-law, and a taboo relationship. he wooed her with love songs whilst making hairstring. A green budgerigar, birds which are commonly found in this area, carried the love song to the woman. When the two lovers came together and made love they turned to stone. They can still be seen at Ngarlu, a site close to Yuendumu. The crosses on the print depict the footprints or tracks left by the green budgerigar. The circular motifs are waterholes.

Artist Profile

COMMUNITY/REGION

Yuendumu, NT

LANGUAGE

Warlpiri

BIOGRAPHY

Paddy Stewart has justifiably been described as a ‘living legend’. He participated in the emergence of Western Desert art in both of its crucial early focal points, the small desert communities of Papunya and Yuendumu. The enforced settlement of different tribal groups at Papunya made for a ferment of discussion and exchange. Paddy contributed to this process that eventually resulted in the groundbreaking Honey Ant mural in 1971. Soon after however, he moved to settle at Yuendumu, one hundred kilometres to the north and closer to his traditional Warlpiri homelands. Here he was instrumental in the art movement that sprang up nearly ten years later, though the manner in which it began was quite different to the struggles at Papunya and resulted in a quite distinctive artistic tone.

Unlike the all male group at Papunya, painting at Yuendumu was initiated by a group of women. There was concern among the elders that the young people were loosing touch with their cultural identity and spiritual roots. In 1984, school principal Terry Davis asked the senior men to join in addressing this educational deficiency by painting ancestral designs on the school doors. Time and space was given to the Aboriginal community to pass on the knowledge about their country; the Dreaming stories and the traditional rites and responsibilities that underpin the Warlpiri identity. It was perhaps this sense of recognition and legitimization by the educational authorities at Yuendumu that helped to fuel the confident, flamboyant style that took the art world by surprise, only recently acclimatized as they were to the more carefully delineated Papunya paintings that were already establishing notoriety around the world.

“My Dreaming is the Kangaroo Dreaming, the Budgerigar Dreaming and the Eagle Dreaming…my son has to teach his sons the way my father taught me, and that’s the way it will carry on into the future, and no-one knows when the jukurrpa will ever end.” (Paddy Stewart in Kleinert & Neale, 2000, p.9) This very specific and personal engagement with the Dreaming challenges the singular meaning that is often assumed by non-Aboriginal people who apply notions of linear time to this timeless space. The Dreaming is an ongoing process of creation rather than an originating moment upon which all others follow. The inherited stories, with their particular attachment to place, plant and animals, carry a responsibility to maintain. The stories elucidate, “a dynamic field of associations within which humans play an essential part”, binding them within ’the Law’ but also giving them a place, an identity and a sense of value. It was the loss of such fundamental qualities that the elders saw their young people suffering from as they attempted to navigate through the new demands and pressures placed upon them by the shift into modern-day schooling and a new way of life. Paddy’s paintings reiterate the narratives of the old ways, conveying their sense of power and grounding, so essential for his people’s survival. (Kleinert & Neale, 2000, p.11)

During his early life, Paddy lived relatively free from European influence but as a young man he began working across the Northern Territory on the cattle stations that were gradually displacing the traditional nomadic life of the Warlpiri people. They were a determinedly cohesive tribe however and ancient traditions were still regularly honoured through ceremony and song. This provided the bedrock of Paddy’s vast knowledge that fed into his painting. Dreaming stories were originally passed down through ground and body paintings but the modern breakthrough was their transposition into modern and permanent mediums. Paddy painted twenty of the thirty-six doors. The vibrant acrylic colours, large brushstrokes and ‘messy’ finish distinguished this ‘eruption of painting’ (Ryan) from the earthy ochres and hard edge precision of Papunya. Although over time the Yuendumu style has refined into a more orderly style, the bright colours and meandering spontaneity has remained a trademark. The doors expressed the passionately independent Warlpiri spirit. No instructions had been given with the new synthetic colours, no aesthetic suggestions or special requirements, the five artists let loose with loud pinks, purples and blues in a confident gestural style, revolutionary and raw but also determinedly political. “We painted these Dreamings on the school doors,” Paddy stated, “because our children should learn about our Law…they might become like white people which we don’t want to happen.” (Ryan, 1989, p69) After the doors were completed, thirteen huge collaborative canvases were painted by the men and brought south for the world to see. After a successful exhibition at the Hogarth Galleries in Sydney 1985, Warlukurlangu Artists was established in Yuendumu in 1986. The association mediates between the desert artists and the commercial art world as well as promoting local artists and cultural programs. Paddy’s ongoing concern for his people and community is reflected in the many roles he has served there, from chairman of the Warlukurlangu committee and community council member to school bus driver and night patrol keeper. He can still be found at the art centre, sitting there working alongside his fellow painter Paddy Simms, “talking and singing together.” (Alfonso, in Petitjean, 2006, p.41)

Although the collaborative nature of Yuendumu art making has often been remarked upon, Paddy’s name was destined for wider recognition when he was selected to create a ground painting installation in Paris for the 1989 exhibition ‘Magiciens de la Terre’. The group received much attention and acclaim and Paddy’s work was there after included in major exhibitions and collections around the world. Back in Yuendumu however, after twelve years of withstanding the harsh desert elements and school children’s graffiti, the doors were bought by the South Australian Museum and in 1995 and taken away for a long period of restoration. Paddy was a key negotiator during this process. He (along with Paddy Simms) was later encouraged by Basil Hall of Northern Territory University to retell the stories in another medium. (Hall, in Petitjean, 2006, p.35) In 2000, thirty small etchings of the same Dreaming stories won the prestigious Telstra Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander National Art Award for works on paper.

© Adrian Newstead

REFERENCES

Kleinert & Neal, Sylvia and Margo, The Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture, Oxford University Press, 2000.

Petitjean, George, (editor) Opening Doors, Aboriginal Art Museum, Utrecht, the Netherlands, 2006

Ryan, Judith, Mythscapes, Aboriginal Art From the Desert From the National Gallery of Victoria, National Gallery of Victoria, 1989

PROVENANCE

Warlukurlangu Artists Cat No. 1443/05

ARTWORK STORY

The country of the Dreaming is garlu east of Yuendumu, near Mount Allen, where a Dreamtime Jungarrayi man (Lintipilinti) fell in love with a Napangardi woman, his classificatory mother -in-law, and a taboo relationship. he wooed her with love songs whilst making hairstring. A green budgerigar, birds which are commonly found in this area, carried the love song to the woman. When the two lovers came together and made love they turned to stone. They can still be seen at Ngarlu, a site close to Yuendumu. The crosses on the print depict the footprints or tracks left by the green budgerigar. The circular motifs are waterholes.

Artist Profile

COMMUNITY/REGION

Yuendumu, NT

LANGUAGE

Warlpiri

BIOGRAPHY

Paddy Stewart has justifiably been described as a ‘living legend’. He participated in the emergence of Western Desert art in both of its crucial early focal points, the small desert communities of Papunya and Yuendumu. The enforced settlement of different tribal groups at Papunya made for a ferment of discussion and exchange. Paddy contributed to this process that eventually resulted in the groundbreaking Honey Ant mural in 1971. Soon after however, he moved to settle at Yuendumu, one hundred kilometres to the north and closer to his traditional Warlpiri homelands. Here he was instrumental in the art movement that sprang up nearly ten years later, though the manner in which it began was quite different to the struggles at Papunya and resulted in a quite distinctive artistic tone.

Unlike the all male group at Papunya, painting at Yuendumu was initiated by a group of women. There was concern among the elders that the young people were loosing touch with their cultural identity and spiritual roots. In 1984, school principal Terry Davis asked the senior men to join in addressing this educational deficiency by painting ancestral designs on the school doors. Time and space was given to the Aboriginal community to pass on the knowledge about their country; the Dreaming stories and the traditional rites and responsibilities that underpin the Warlpiri identity. It was perhaps this sense of recognition and legitimization by the educational authorities at Yuendumu that helped to fuel the confident, flamboyant style that took the art world by surprise, only recently acclimatized as they were to the more carefully delineated Papunya paintings that were already establishing notoriety around the world.

“My Dreaming is the Kangaroo Dreaming, the Budgerigar Dreaming and the Eagle Dreaming…my son has to teach his sons the way my father taught me, and that’s the way it will carry on into the future, and no-one knows when the jukurrpa will ever end.” (Paddy Stewart in Kleinert & Neale, 2000, p.9) This very specific and personal engagement with the Dreaming challenges the singular meaning that is often assumed by non-Aboriginal people who apply notions of linear time to this timeless space. The Dreaming is an ongoing process of creation rather than an originating moment upon which all others follow. The inherited stories, with their particular attachment to place, plant and animals, carry a responsibility to maintain. The stories elucidate, “a dynamic field of associations within which humans play an essential part”, binding them within ’the Law’ but also giving them a place, an identity and a sense of value. It was the loss of such fundamental qualities that the elders saw their young people suffering from as they attempted to navigate through the new demands and pressures placed upon them by the shift into modern-day schooling and a new way of life. Paddy’s paintings reiterate the narratives of the old ways, conveying their sense of power and grounding, so essential for his people’s survival. (Kleinert & Neale, 2000, p.11)

During his early life, Paddy lived relatively free from European influence but as a young man he began working across the Northern Territory on the cattle stations that were gradually displacing the traditional nomadic life of the Warlpiri people. They were a determinedly cohesive tribe however and ancient traditions were still regularly honoured through ceremony and song. This provided the bedrock of Paddy’s vast knowledge that fed into his painting. Dreaming stories were originally passed down through ground and body paintings but the modern breakthrough was their transposition into modern and permanent mediums. Paddy painted twenty of the thirty-six doors. The vibrant acrylic colours, large brushstrokes and ‘messy’ finish distinguished this ‘eruption of painting’ (Ryan) from the earthy ochres and hard edge precision of Papunya. Although over time the Yuendumu style has refined into a more orderly style, the bright colours and meandering spontaneity has remained a trademark. The doors expressed the passionately independent Warlpiri spirit. No instructions had been given with the new synthetic colours, no aesthetic suggestions or special requirements, the five artists let loose with loud pinks, purples and blues in a confident gestural style, revolutionary and raw but also determinedly political. “We painted these Dreamings on the school doors,” Paddy stated, “because our children should learn about our Law…they might become like white people which we don’t want to happen.” (Ryan, 1989, p69) After the doors were completed, thirteen huge collaborative canvases were painted by the men and brought south for the world to see. After a successful exhibition at the Hogarth Galleries in Sydney 1985, Warlukurlangu Artists was established in Yuendumu in 1986. The association mediates between the desert artists and the commercial art world as well as promoting local artists and cultural programs. Paddy’s ongoing concern for his people and community is reflected in the many roles he has served there, from chairman of the Warlukurlangu committee and community council member to school bus driver and night patrol keeper. He can still be found at the art centre, sitting there working alongside his fellow painter Paddy Simms, “talking and singing together.” (Alfonso, in Petitjean, 2006, p.41)

Although the collaborative nature of Yuendumu art making has often been remarked upon, Paddy’s name was destined for wider recognition when he was selected to create a ground painting installation in Paris for the 1989 exhibition ‘Magiciens de la Terre’. The group received much attention and acclaim and Paddy’s work was there after included in major exhibitions and collections around the world. Back in Yuendumu however, after twelve years of withstanding the harsh desert elements and school children’s graffiti, the doors were bought by the South Australian Museum and in 1995 and taken away for a long period of restoration. Paddy was a key negotiator during this process. He (along with Paddy Simms) was later encouraged by Basil Hall of Northern Territory University to retell the stories in another medium. (Hall, in Petitjean, 2006, p.35) In 2000, thirty small etchings of the same Dreaming stories won the prestigious Telstra Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander National Art Award for works on paper.

© Adrian Newstead

REFERENCES

Kleinert & Neal, Sylvia and Margo, The Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture, Oxford University Press, 2000.

Petitjean, George, (editor) Opening Doors, Aboriginal Art Museum, Utrecht, the Netherlands, 2006

Ryan, Judith, Mythscapes, Aboriginal Art From the Desert From the National Gallery of Victoria, National Gallery of Victoria, 1989